Canberra’s growth—an overview

The city of Canberra is located in the Australian Capital Territory, a 2,356 square kilometre area of land handed over by the NSW government in 1911 for the site of Australia’s new capital. The Territory is a hilly environment containing much natural bushland. The tree-clad, landscaped city itself has been described by architecture historian Jennifer Taylor as “a vast garden containing buildings as individual objects.”

The 1930s and 1940s

Canberra’s beginnings as a planned city established conditions that were different from Australia’s other major cities. Early development came in fits and starts, with government indecision, World Wars and the Great Depression severely limiting the amount of public building undertaken before 1950. Canberra was little more than a country town during the 1930s, with a population of around 10,000. In 1941 there were as few as 400 privately owned houses, with the vast majority of housing construction government driven.

What of modernism in Canberra during this period? The ideas of mainstream modernism came slowly to Australia and there was little private building activity in Canberra during this period. There were probably only two privately practising architects in Canberra up until the late 1940s—Kenneth Oliphant and Malcolm Moir—and aside from government architects Cuthbert Whitley and E H Henderson there was little apetite for the ideas of European modernism. Consequently, only a very small number of inter-war functionalist houses survive from this period, some being influenced by the architecture of Mies van der Rohe in Germany and W M Dudock in Holland.

Incidentally, Federal Capital Commission architecture from the 1920s and 1930s is unique to Canberra—but is not examined on this site. The best coverage of FCC architecture can be found in The Early Canberra House 1911-1933, edited by Peter Freeman.

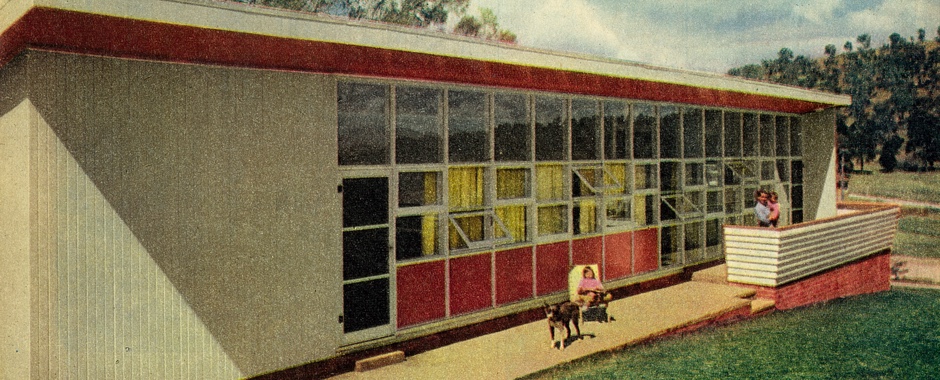

The 1950s

The population of Canberra grew to 50,000 during the 1950s. The decade saw the establishment of the Australian National University, gradual movement of Federal government departments to Canberra and the creation of the NCDC in 1957. The arrival of academics and senior government officials from Sydney and Melbourne accompanied these developments and it was not unusual for them to commission architects from their home cities to design their new houses in Canberra. The presence of post-war Sydney and Melbourne streams of modernist residential architecture together is unusual and seldom found elsewhere in Australia.

At the same time, the NCDC increased the amount of commissioned government work for public building, also attracting leading architects to Canberra. As a result of these influences, there are some excellent examples of post-war Melbourne (Grounds and Boyd) and post-war international architecture (Sydney architects Seidler and Ancher) from this period in Canberra, some of national importance.

[Canberra is] … a vast garden containing buildings as individual objects.

In Experiments in Modern Living: Scientists and the National Capital Private House 1925-1970, Milton Cameron has examined how a group of scientists, brought to Canberra to take up leading roles in the establishment of national scientific institutions, commissioned private houses that rejected previous architectural styles and wholeheartedly embraced modernist ideologies and aesthetics.

The firm Grounds, Romberg and Boyd established an office in Canberra, located in one of the Forrest Townhouses designed by Grounds. Roy Grounds, for example, who designed the Australian Academy of Science building formed relationships here with prominent scientists such as Sir Otto Frankel, and later designed Frankel’s house in Campbell.

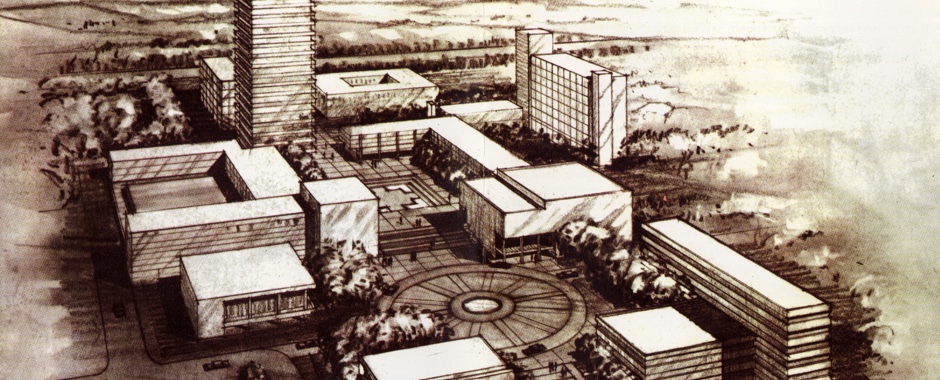

The 1960s

With the NCDC in full swing, and Canberra resembling a construction site, the 1960s witnessed growth rates of 10% per year and by 1970 the population had climbed above 140,000. The city was transformed, with the development of new satellite towns in Woden and Belconnen, the creation of Lake Burley Griffin and the commencement of national institutions in the central national area. Notable buildings completed for national and community institutions include the Academy of Science (Roy Grounds, 1958) and the National Library of Australia (Bunning and Madden, 1967). The decade saw further important examples of Melbourne regional and post-war international architecture designed and built, together with the emerging Sydney regional style and beginnings of medium density housing. The first medium density housing development sponsored by the NCDC in Swinger Hill created a sensation when it was opened for exhibition on two weekends in April 1972, attracting over 20,000 visitors.

The major developments in Australian post-war architecture are well represented in Canberra’s houses of the 1960s:

- The post-war Melbourne regional architecture of Roy Grounds and Robin Boyd

- Examples of post-war international style houses from Harry Seidler

- Sydney regional architecture by Ian McKay, Allen, Jack and Cottier and Ken Woolley

- The organic architecture of Enrico Taglietti

The 1970s and 1980s

Canberra’s high growth rate continued in the early part of the decade and large scale office development accompanied a rapid expansion of the town centres in Belconnen, Woden and Tuggeranong. By 1976 the population had reached 203,000. The Sydney regional style became more widespread in the early part of the decade, particularly in developing bushland suburbs such as Aranda. The 1970s also saw a further increase in medium density development as the NCDC began actively promoting the idea of townhouse living.

The city of Canberra matured in the 1980s, with the population approaching 300,000 and greater diversity apparent in lifestyles, employment and recreation. The suburbs and town centre of Tuggeranong were constructed to the south, and the new town centre of Gungahlin planned in the north. Meanwhile, real estate values in inner suburbs increased significantly, reflecting a growing awareness and appreciation of the city’s history and heritage. The marked increase in the regeneration of central suburbs has provided opportunities for architects, and produced a number of interesting and award winning houses in this period. But it’s a two-edged sword: this regeneration also threatens some significant older houses with demolition and redevelopment.