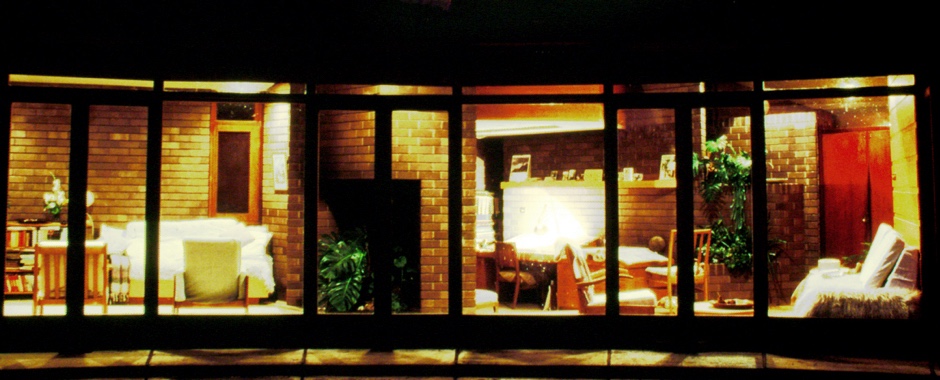

‘Rivendell’, 17 Meredith Circuit, Kambah (1975)

‘Rivendell’, the house at 17 Meredith Circuit, Kambah was designed by Laurie Virr for his family in 1975 and substantially built with his own hands. It is a rare Canberra example of the late twentieth century organic style of architecture based on a hemicycle. Laurie Virr has designed work in the United States, New South Wales and Victoria, along with a number of houses in Canberra.

Significance

The house is an outstanding example of the late twentieth century organic style with its massing, use of geometric forms, deep roof overhang and energy efficient design. The successful implementation of a complex geometric plan based on a hemicycle is unusual if not unique for a mid-century Canberra house. The house has been published many times, in the U.S.A., Europe and Australia. Inexplicably, it is relatively unknown in Canberra.

Description

The house is sited to reap the benefits of solar access, facing north on a suburban lot of 1108 square metres on the north side of Meredith Circuit, Kambah. Halfway up a hill, the site slopes down at 1:6 for the first 10 metres of its depth, the gradient then easing to 1:8 for the remaining distance to the rear lot line.

The brief for Rivendell stipulated the requirements of the family: areas for living and dining, two small, but adequate bedrooms, a studio, kitchen, laundry-utility, bathroom, and a carport capable of sheltering a small car—at just over 123 square metres, a modest, clever, energy efficient design.

The house is based on a hemicycle—an architectural planning device that has been employed since Ancient Egypt and used by Bruce Goff, Frank Lloyd Wright, Donald Reed Chandler, John Randal McDonald and Charles Montooth in designs for twentieth century houses. All these latter designs used the hemicycle in conjunction with other elements, either circular or rectilinear. In 1975, however, combining the arcuated form with triangular and hexagonal elements was unique.

The aim was to design a house in which the siting, exploitation of space, the massing, the concern for the environment, and the details, expressed in unequivocal terms what I considered to be Architecture.

The house faces E 10° N, allowing more sun in Spring and less in the Autumn. Experience since has shown this to have been a minor error of judgement, inasmuch as some days the valley is shrouded in fog until noon. An orientation of W 15° N would maximise the opportunities of solar gain on such days. At Latitude 35° 23’ the useful sun at the winter solstice occurs between the hours of 9am and 3pm, a quarter of its daily path, and nominally 90°.

The ground plan is really a very simple idea: an arc terminating in polygons, with a two-storey central hexagonal mass anchoring the whole composition. The terminals also extend in height above the lower ridge line and all three masonry masses are embraced as they penetrate the sheltering roof. In further aspects of architectural expression, each space is articulated in both ground plan and elevation. The interpenetration of forms, both horizontally and vertically, makes manifest the architectural expression of the individual spaces, and the broad roof overhangs gratify the sense of shelter. The French doors and stationary glass on the north face of the house encompass an arc of 90°, making it an architectural expression of the problem. This is also exemplified by the walls that define the terrace and mark the extent of the glazing.

The living, dining, kitchen and studio are small areas in themselves, but they are arranged in such a manner that they borrow from each other, and together with the mezzanine bedroom, form one horizontal and vertical space. Moreover, the hemicycle form of the body of the house, and the disposition of the terminals is such that it is difficult to determine the extent of the space, for there always appears to be something beyond what is immediately visible.

The house is effectively one room wide, with very little area dedicated solely to circulation space. Unlike many so called solar houses that have warm living areas to the north, and very cold bedrooms to the south, the ground plan allows most of the walls and floors to act as solar collectors. During winter the sun strikes a wall of the main bedroom as soon as it rises above the hill to the east in the morning, and is still shining in the area of the dining table, at the other end of the house, late in the afternoon. The masonry alone—30,000 bricks—furnishes 120 tonnes of mass, and this is enhanced by that of the insulated concrete floor slab. Provision is made for cross-ventilation during the summer months, while the eaves and heavily insulated roof ensure that the effects of the sun are excluded during the warmest time of the year.

The construction materials are predominantly face brick masonry, wood casement sash and French doors, a colored concrete floor slab, trowelled smooth, and grooved along the lines of the module, and glass. Almost all the furniture is of wood, and built into the structure, with custom made upholstery for the bench seat. Colors used in the house blend with landscape and the landscaping of the site displays the same concern for the environment as does the house. The planting is predominantly comprised of trees, shrubs and groundcovers native to the immediate region.

Source

- Conversations with and information provided by Laurie Virr

- M. Parnell and G. Cole, Australian Solar Houses (1983)